An Interview with Paul Bott by Rosalyn Frances

On a sunny Friday in June I meet Paul Bott, one of Artbox's long-time members. Whilst perusing his extensive portfolio, I am struck by the intensity of his work, both in terms of depth of colour as well as his preference for traditional media and working methods. For example, he has painted multiple tempestuous landscapes often riven with purple and blue (some of his favourite colours) and seething with dynamic brushwork. These are underscored by an internal angular geometry and recall the paintings of both the post-impressionists and the fauvist group. Whilst he also works in acrylics, watercolours, and oil pastels, oil paint is by far his favourite medium. “Oil paint makes a more profound effect,” he notes. Then, as an aside, “it’s what all the professional artists use, isn’t it? Van Gogh, Picasso.”

He refers to a painting which is meticulously rendered on canvas board, listed on the website as Untitled 6. The painting depicts a traditional Mask in the form of the scull, vibrantly coloured with a rich patina of scalloped lines, bands of decoration and diamonds overlaid with crosses. The scull appears as if backlit with yellow light and the tangibly textured background bears the mark of a layer of red paint overlaid with white. It is indicative of his oil paint technique, he notes, as it has been carefully built up in layers.

How long does it take to make something like this?

“A week, two weeks, three weeks. It depends. With watercolour you can do it in an hour, half an hour. Acrylic you can do in an hour. With oil you have to wait for it to dry and it’s more difficult.”

I get a sense that the difficulty is part of the attraction. Paul clearly gets pleasure from the gradual process of learning a skill, before achieving a level of mastery in it and being able to add it securely to his artist’s toolbox. When I remark on the impressive nature of his oil paint technique, he replies hastily: “they look professional, but I am taking a long time to develop the style. To [make them] look more professional.”

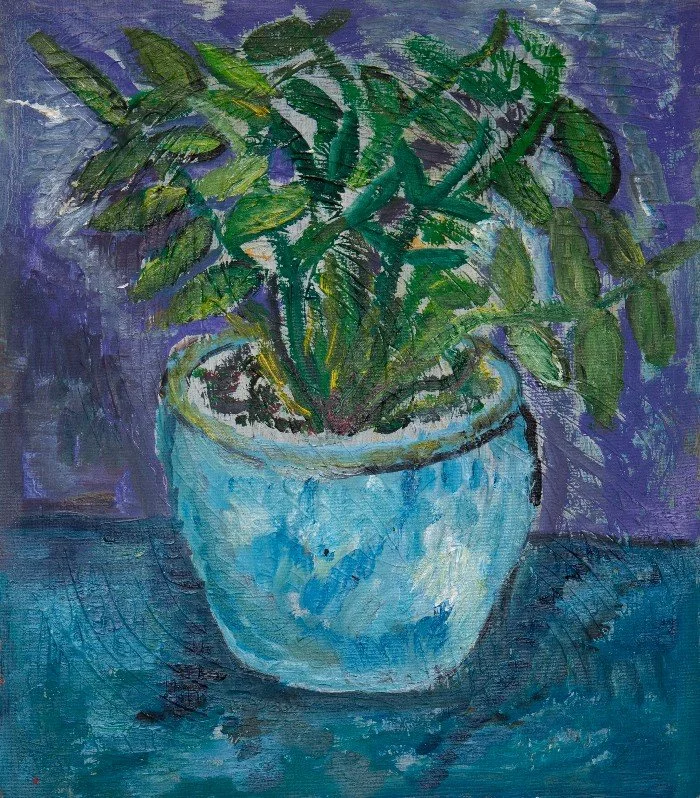

Although diverse scenes populate his artwork, from domestic living room subjects to zany studies associated with history and his passion for the Vikings, his most recent output has been focussed on the natural world. “Plants” inspire him, he says. As do “tropical islands, landscapes, things like that.”

“I love nature. Anything that is easy to paint because painting people, buildings is quite difficult. Animals are quite difficult.”

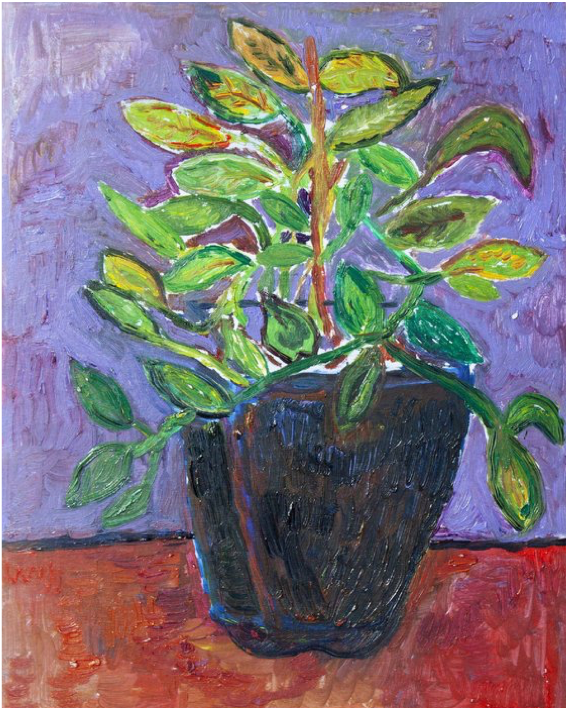

Paul is modest - nature is certainly not universally regarded as simple to portray. Yet the ease and familiarity that he has with this subject matter is indeed in evidence in his work. His recent painting, Parlour Palm, which depicts a verdant indoor plant in front of an electrically vivid lavender wall, featured as part of a charity auction; the auction was hosted by the charity Islington Giving. In this painting, Paul has rendered the leaves of the pot plant fluidly and confidently, and they appear to reach out as if to communicate with the viewer. The plant looks more alive than any plant I have personally taken home (and certainly more alive than any plant left in my keeping!)

Parlour Palm, sold

The painting is also reminiscent of the work of Paul’s favourite artist Vincent Van Gogh. The contrasting tints of orange amid the olive-green leaves here call to mind the way in which Van Gogh tended to add extensive highlights and flourishes to his vegetal subjects. In, for example, the painting Oleanders, 1888, lines of orange, whites, and creams are set together in the petals of the flowers. These sketchy marks merge, when viewed holistically – this creates the impression of cohesive blooms. In both artists’ work, the graphic, linear use of the paint brush draws attention to the plant, pulling the foliage/ flowers firmly into the foreground. Paul, in particular, has a tendency towards to painting plants or objects that feel very animated, almost as if they are the subjects of a “portrait”.

Vincent Van Gogh, Oleanders, 1888, oil on canvas, 60.3 x 73.7cm (New York: The Met Museum). Image source: www.metmuseum.org

Later in our conversation he also tells me that he loves David Hockney’s work, although I don’t have time to question him further about this interest. I do, however, ask Paul what he finds most exciting about Van Gogh. He answers concisely. “His bright colours, his tones and brush strokes… It is the kind of impressionistic way things are portrayed.”

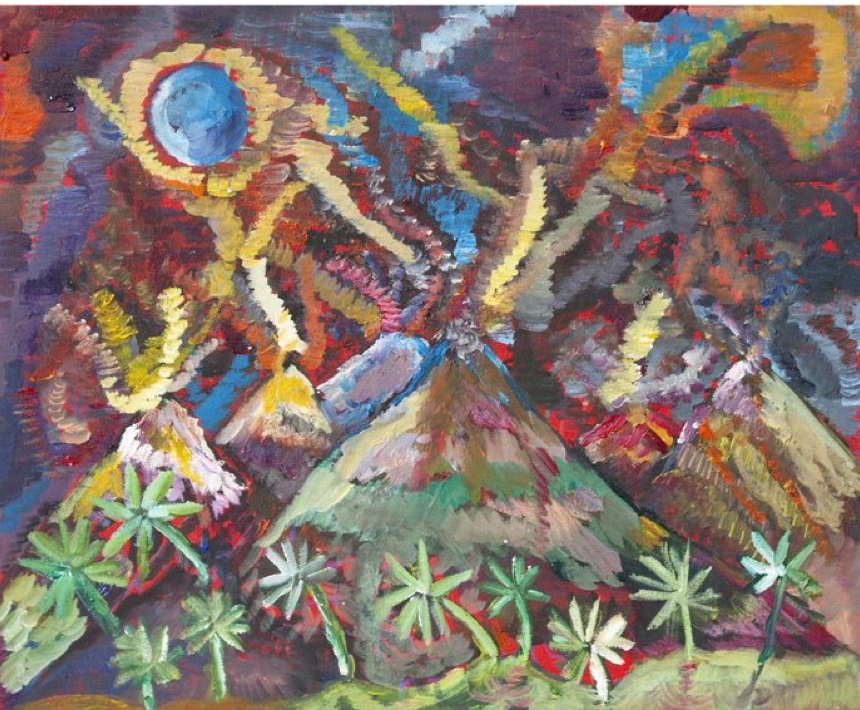

Some of Paul’s paintings are intense and observational, and Parlour Palm is certainly an example of this category. However, in other paintings, for example in Desert Island, or Untitled 1, triangles are created out of the mountains, and colours stream with abandon, and so the effect is looser and less representational. I wonder how/ why Paul chooses to make a painting more, or less, abstract. On occasion, he notes, it is his imagination that rules the roost; “Sometimes it is from my head.” However, “sometimes I paint a flower and a bush, and I really look at it and try to make it as realistic as I can. Sometimes it is like a photograph, I try to make it look like a photograph.”

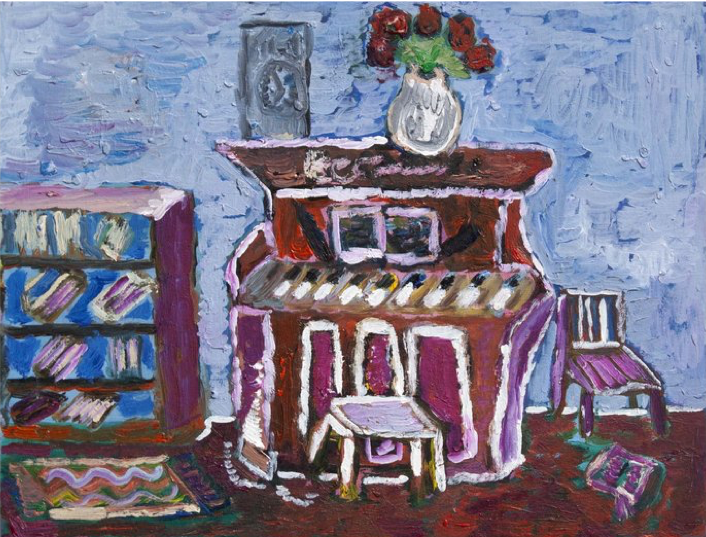

He draws my attention to one of his favourite paintings, Untitled 3, which, as it depicts a piano, unites his dual passions of music, in particular rock and classical, and the visual arts. The painting is based, he tells me, on the piano on his living room, which, although he doesn’t play, he lives with, and so is fond of. Much the same as with Parlour Palm, in this painting Paul is deft in his handling of the oil paint, and his movement from darker to lighter colours in the layering process is observable. This is significant – it gives even the walls in the painting the appearance of perpetual vibration.

I ask Paul if music provides creative fuel for his artmaking. He hesitates, before replying simply, “yeah, kind of, the lyrics of Freddy Mercury.” He does not elaborate further on this, although given Mercury’s fame, my imagination begins to run wild. I reason that Queen Lyrics would work as stellar captions for some of Paul’s paintings. Subsequently I choose to put a couple of lines of Queen’s iconic 1995 hit, Made in Heaven, with Paul’s tropical landscape (below).

Towards the end of the interview, I ask him if there is anything important that I have not asked him. He immediately notes that I have not inquired how long he has been making art, and so I ask. “I began drawing at school. People usually ask me this first… I left school and then I did A levels at college… College was quite good, I guess. I did learn about still life.”

He pauses, before continuing: “art doesn’t make a lot of money.”

I concur - it has always been difficult to make a living as an artist, and the past couple of years and the pandemic have exacerbated this.

“I do like art. But the government,” he says resignedly, “encourages you to be a doctor or an engineer or a lawyer… Since the pandemic… being an artist wasn’t [seen as] essential.”

But art is essential, we agree. Art brings joy, as well as providing purpose and community. Art is also a way of being alive to your surroundings, it’s a kind of mindfulness. Paul puts it well “Art is about observing the world around you.” What could be more essential than that.